Photo © Geoff Brown

(L-R) Pete the Punk and Bernie Wilcox.

Bernie Wilcox writes:

My memories of 1977 were that the NF were gaining ground strongly with them polling over 5% of the vote in that year's GLC elections which was over 120,000 votes. They were very confident and people just didn't associate them with Nazis although there were pictures available of their leaders, Webster and Tyndall, dressed up in Nazi uniforms. They were not only on the streets but they were making physical attacks on the left, Jews and people of colour including regular petrol bombings.

Into this atmosphere, Eric Clapton went on a rant at a concert in Birmingham. It's worth repeating his whole rant because it's just so shocking.

“I don’t want you here, in the room or in my country,” Clapton said. “Listen to me, man! I think we should vote for Enoch Powell. Enoch’s our man. I think Enoch’s right, I think we should send them all back. Stop Britain from becoming a black colony. Get the foreigners out. Get the w*gs out. Get the coons out. Keep Britain white. I used to be into dope, now I’m into racism. It’s much heavier, man. F***ing wogs, man. F***ing Saudis taking over London. Bastard w*gs. Britain is becoming overcrowded and Enoch will stop it and send them all back. The black w*gs and c**ns and Arabs and fucking Jamaicans and fucking… don’t belong here, we don’t want them here. This is England, this is a white country, we don’t want any black w*gs and c**ns living here. We need to make clear to them they are not welcome. England is for white people, man. We are a white country. I don’t want f***ing wogs living next to me with their standards. This is Great Britain, a white country. What is happening to us, for f**k’s sake?”

That rant started off Rock Against Racism but the anti NF protest at Lewisham in 1977 was pivotal in aligning the music press with anti racist politics. Tony Parsons and Julie Birchall were the punk reporters on the NME and they persuaded the editor to do a middle page spread on the Lewisham protest. Melody Maker and Sounds fell into line and all the music press were all of a sudden, interested in politics and were anti racist.

It's interesting to read Tom Robinson's lyrics of his Winter of 79 track released in early 78 which gives a flavour of where the left were at that time. We really did feel like we were on the back foot.

The first Carnival in London changed all that. We felt for the first time in ages that we were far bigger and stronger than the Front. Both we and the Front were amazed that we mobilised 80,000 anti racists onto the street and it was a massive shot in the arm for us. We suddenly felt like the wind had changed direction. After he played 79 at the first Carnival, Tom said, "I wrote this about what I thought was going to happen in 1979, but after today, it hasn't got a chance."

It had a massive effect on me and Geoff as well. We had three coaches that went from my Manchester overspill estate, Partington that day, but I managed to miss all of them and ended up bumming a lift on the special train back to Manchester where I sat with Geoff. I can't remember if he said it to me or I said it to him, but we agreed that we'd have to do one in Manchester.

Even (or maybe in particular) on the left, politics was very London-centric then and those in the capital didn't really understand that not every anti racist from Burnley or Preston or Salford wanted to travel to London. We wanted a Carnival of our own as The Clash might have sang.

It seems incredible now with all the rules and regulations we have that we could put together such a massive march and free gig in just 10 weeks, especially as both Geoff and I had full time jobs. Of course, you could get away with doing very little in those days. I was working as a structural engineering designer at Shell Carrington and I basically spent my day doing a nominal bit of work and organising the Carnival and other RAR gigs plus other protests like a campaign against education cuts in Trafford where the Tory council were threatening to close the local youth club in Partington. In a place with a population of 7,000 that had just 3 pubs and a last bus that left Piccadilly at 11 at night, the youth club was the only place for the kids to go to and the Tories wanted to take that from them.

The guys in the office used to answer my phone saying, "Bernie's carnival office."

Of course, it wasn't just me and Geoff. There were loads of great people who did lots of work getting things organised and I had a credibility issue being just 22 at the time. I only owned one suit and it was brilliant white. We went for a meeting at the town hall to get them to give us permission to use Alex Park. Geoff took one look at me and said, "Christ Bernie. How are we supposed to get them to take us seriously when you turn up looking like John Effing Travolta?" Saturday Night Fever had just been released but I'd had my suit for about a year before that.

Everyone wanted to do something to help and we had phone calls every day from activists and people quite new to politics wanting to lend a hand.

In the weeks leading up to the Carnival things just mushroomed. There was a massive buzz around the city and the punk thing about wearing badges had transferred to the population in general, and they were all wearing our badges!

NF = No Fun, skateboarders against the Nazis, Gays against the Nazis, Firemen against the Nazis. Loads of different ones. It seemed like everyone walking down Market Street on a Saturday was wearing Anti Nazi badges.

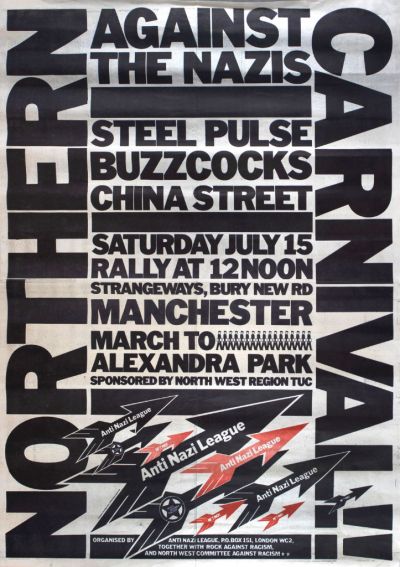

Getting the bands was pretty easy apart from the Buzzcocks who just wouldn't commit at all. We definitely wanted the Buzzers. Not only were they part of the original punk movement but their punk pop had breached the ramparts of the regular music scene with them appearing on Top of the Pops and releasing their second Top 40 single just a few weeks before the Carnival. Mark Smith asked them for me to no avail and then as luck would have it, I bumped into Pete Shelley coming out of a musical instruments shop on Oxford Road. I collared him there and then and asked why they wouldn't commit to the gig. He was great, committed there and then and their manager called me the next day to confirm. Phew!

The other problem was every other band wanted to play and we couldn't have them all. Some got a little upset about it including The Fall. It was difficult because playing to 200 people at The Squat wasn't the same as 40,000 in the open air and many of the bands that wanted to play just didn't have the experience or the presence to carry it off.

As you can imagine, I was a bit busy on the day pulling things together and trying to resolve ego issues. Even the photographers were arguing about who had the best spot and there was a discussion about who should play last. The Buzzcocks said that they thought that Steel Pulse should get the top slot which was very nice of them because although Steel Pulse had just supported Marley on tour, they weren't anything like as big as the Buzzers then.

What difference did it all make?

When I look at my kids and their friends today, racism is just something that they won't tolerate. Watching City, there used to be lots of racist comments about black players. These days, the crowd would shut those people up. I hope that in our little way, the people who attended the Carnivals, the gigs, the protests and marches, have brought their kids and their kids' kids to be naturally anti racist and have contributed to the progress we've seen so far.

The battle isn't won however. I still see Facebook posts from people supporting Tommy Robinson's right to be in contempt of court or reposting some nonsense from Britain First. I've been in the recruitment industry for 35 years and I still see candidates with obviously black or Asian names not getting the same chances as those with white names. Although we have lots of black footballers we have very few black coaches and managers.

Some musicians and fans in Manchester have organised a gig in commemoration of the Carnival and it's great to see 20 year olds interested in politics and getting things together. We can't ever relax on this stuff.

Curated by Abigail Ward.

Curated by Abigail Ward.