Exhibition

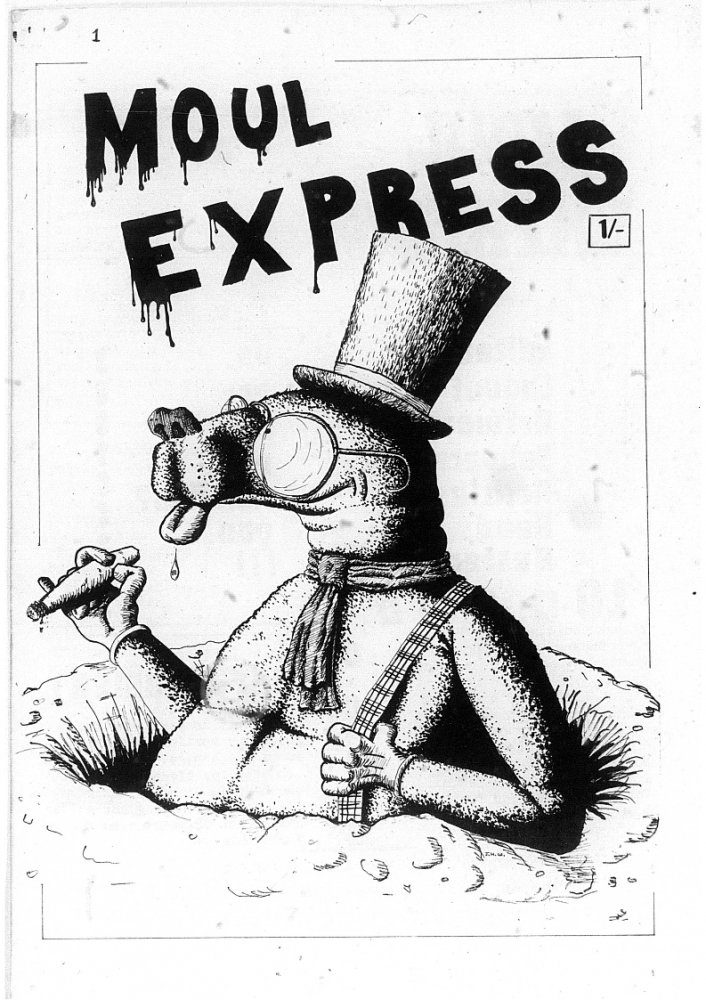

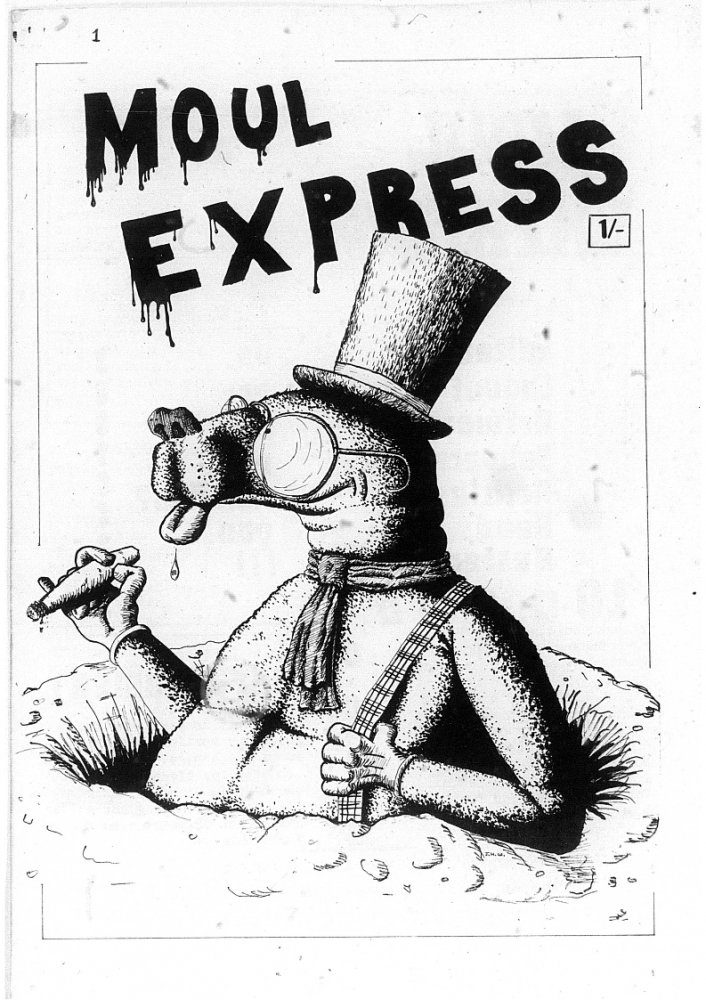

Mole Express - A Magazine for Manchester's Counter Culture

Mole Express was a truly alternative, grass-roots publication first issued in 1970 which ran for seven years. Throughout its 57 issues the modern reader catches a glimpse of the anarcho, post-hippy subculture in Manchester (and sometimes wider afield).

It followed on from the 60s publication Grass Eye and heralds the birth of the On the 8th Day cooperative (still going strong in 2020) and issue 4 includes a poem by (a presumably then unknown) John Cooper Clarke.

Contributors included Cp Lee, Martin Hannett and Roger Eagle.

Please note that in our collection issues 26, 27, 41 and 42 are missing. The final issue, no. 57, is incomplete.

Thanks to University of Brighton Library collections for providing the original scans.

Mole Express – an introduction and a celebration by Dave Haslam

The musical and spiritual home of the Manchester freak scene at the end of the 1960s, was the Magic Village, a venue founded by Roger Eagle who had formerly been instrumental in the success of the Twisted Wheel. He’d left the Wheel, impatient to move on musically, inspired by the likes of Captain Beefheart.

In a dark cellar on Cromford Court (now buried somewhere under the Arndale Centre), the Magic Village hosted emerging progressive bands including the Groundhogs, the Edgar Broughton Band (several times), and Van Der Graaf Generator (one of their first ever shows).

The opening night in March 1968 featured Jacko Ogg & the Head People (the band included CP Lee and Bruce Mitchell in the line-up). Across town at the Twisted Wheel, the scene that was evolving into Northern Soul was fuelled by amphetamines, but in the world Roger was now connected to the drugs of choice were hashish and LSD.

One of Roger Eagle’s most intriguing concepts was to invite to Mike Don to set up a stall selling underground newspapers in the Magic Village every Saturday night. Mike was a music fan, a friend of Roger’s, who had started street selling Manchester University’s alternative newspaper ‘Guerilla’ on the steps of the Student Union.

In Britain in the last years of the 1960s and the beginning of the following decade, the pages of underground newspapers like International Times, Oz, Frendz, and Ink! reflected and shaped news of a newly emerging counter-culture of non-conformity, drug use, and – as ‘hippie’ turned into ‘yippie’ – oppositional politics. Anti-Vietnam War campaigns were a constant preoccupation, second only to information about drugs, their side-effects, and how to avoid getting busted.

According to Mike Don, the kind of people who would go to Roger's club buy International Times, would have called themselves as “freaks”. We also discussed freaks who enjoyed underground music and were also politically engaged; this seemed to be Mike’s chosen sub-division; he identified himself alongside other “acid-head lefties”.

Mike’s involvement in the underground press moved up a level following a conversation with one of the Magic Village’s regular attendees, a young man called Chris Dixon who had started an underground paper called Universal; with the input of several other people - including Mike Don - this became Grass Eye. Mike didn’t last long on the editorial group but wrote for it on a fairly regular basis, including reporting on Anti-Apartheid protests when the South African team played in Manchester in November 1969.

At the end of 1969 Grass Eye folded, temporarily, because it was short of money. Over the next few months, a couple of people who’d been working on Grass Eye, Sue Lear and Steve Curry, began planning a new paper, called Moul Express. They contacted Mike and asked him to be a part of it.

The very first issue of Moul Express was published in May 1970. Running through the sixteen black and white pages is a list of who the paper was “Written by and for”. The list includes ACID-FREAKS AGITATORS ANARCHISTS ANGELS APPRENTICES ARTISTS ATHEISTS BLACK PANTHERS COMMUNARDS DEVIANTS DOSSERS DRUGTAKERS DROPOUTS FLATEARTHERS HIPPIES HOMOSEXUALS INDIANS MAD BOMBERS.

In the introduction below that Mike Don penned for the Manchester Digital Music Archive, he explained why the name changed to Mole Express after six issues.

The final Mole Express was published in 1977; fifty-seven issues in seven years. Coverage of race in the early phase included more on Anti-Apartheid, plus solidarity with the Black Panthers in America; later issues went to war against the National Front. Education was always a battleground. Housing was a major concern in the first few issues of ‘Mole’; and stayed close to the front of the agenda throughout its publishing history. In 1970 there was anger over the way the Council had denied the local community a meaningful voice when they delivered their ‘slum clearance’ plans in areas including Moss Side and Hulme.

Early issues featured an article on Sun Ra and interviews and news from local bands including Greasy Bear (the line-up included CP Lee and Bruce Mitchell post-Jacko Ogg & the Head People), and, through its history, cartoons by the likes of Peter Kirkham, Bill Tidy, and Tony Husband. Issue 4 included a poem by John Cooper Clarke, possibly his first published work.

The content was eclectic, passionate. In 1974, in one of the first books to document the underground press in Britain, Mole was said to provide “an exceptional picture of alternative arguments in action in Manchester”.

The Magic Village closed at the beginning of 1970. During the Summer of 1970, Mole kept readers updated on the goings on at a venue in Manchester called Mr Smiths, where the team from Grass Eye had been running an event they called ‘Electric Circus’ every Sunday.

Mole also gave news of DJs around the city who played progressive music; less than a handful, basically. At Oceans 11, a venue that had previously been Birch Park Skating Palace, Tuesdays were recommended (they were hosted by DJ Chinese Pete). The paper also recommended Auntie’s Kitchen on Bow Lane, off Clarence Street. Adverts for weekend nights promised “Underground Sounds”, “Freak lights” and “Exotic dancers”.

The bigger, London-based, underground papers had an international outlook, but weren’t much interested in goings-on elsewhere in the country. Mole Express embraced the chance to be hyper-local; one report details how two men were arrested at the Plaza curry house on Upper Brook Street after police surveillance from the house opposite. The arrested men were both waiters from the café, identified in Moul as ‘Manny’ and ‘Basho’.

Manchester interests jostled alongside international issues. Moul issue 4 included a page devoted to explaining and celebrating the Weather Underground (a network of leftists which had declared war on President Nixon, the US Government and big business after state troopers had killed four unarmed Anti-Vietnam protesters at Kent State University in May 1970). The Weather Underground are the vanguard, Moul declared; “the spark that will create the situation that will lead to total revolution”.

Moul Express had a take on the General Election of June 18th 1970; explaining to readers that refusing to vote is the only course to take, called for ”active sabotage”, dropping cigarette butts into the ballot box, writing-in votes for Edgar Broughton. “There is only one way out. FUCK IT UP. At the very least spoil your ballot paper. Vote YIPPIE! Vote for the All-Night Party.”

After the Magic Village, Roger Eagle began to promote shows at a former boxing and wrestling stadium in Liverpool – Moul sent a reviewer to the first of these, which featured the Edgar Broughton Band, Kevin Ayres, and the 3rd Ear Band. Roger’s Stadium gigs frequently had advertising space in subsequent issues.

As with all magazine archives, the advertisements in Mole Express are as intriguing as the editorial content. Examples include the Black Sedan record shop on All Saints, Grass Roots Books (where Mike Don worked daytimes), gigs at UMIST and the University Union, On the 8th Day, and Gold Seal (a second-hand jewellery, clothes and record store near the Plaza).

As I describe in my small format book

‘All You Need is Dynamite: Acid, the Angry Brigade, and the End of the Sixties’, political attitudes were hardening in many parts of the world, not just the USA. Revolutionary leftist terror groups were active in Germany and Italy by 1971.

In Britain, the Angry Brigade were responsible for dozens of bomb attacks on various properties (including banks, the homes of Tory Cabinet ministers, embassies, and army recruitment centres) . The mainstream media complied with instructions from the authorities to censor news of these incidents though, leaving the underground press to hint at what was happening. Mole Express seems to have very good sources among anarchist and leftist groups. On one occasion, the paper reported two violent actions carried out locally, including a petrol bomb attack on a police car on Northern Grove, close to Withington Hospital, and an attack on an electricity sub-station in Altrincham.

Mike Don recalls that at least two Angry Brigade members lived in Moss Side for a while prior to arrest in London which broke the back of the organisation; and that they contributed to Mole. This episode in Moss Side I investigate in my book at length. Most articles were anonymous, so it’s hard to confirm who authors were, although we know the music coverage contributors included Roger Eagle and Martin Hannett.

As Mike wrote in 2018; “Early Mole had been ferociously anarchist, even Situationist... but by 1975 the material was local and investigative”. Favoured issues included Town Hall corruption, further problems in education and housing, and a need for community action. “It’s about time we got together and made our city liveable in” one writer demanded.

After his time staging gigs at the Stadium, Roger Eagle, booked bands into the Liverpool club Eric’s, which became an inspiration and a catalyst for Liverpool’s glorious post-punk scene. He later took over the International on Anson Rd in Manchester; that same venue where Chinese Pete had wowed the progressive music fans in 1970.

Mole was influential on at least one of the prime movers behind the Manchester fanzine City Fun, the subject of this

online exhibition, Liz Naylor described it as “'the greatest magazine ever'.

Mike Don died in May 2021. This Manchester Digital Music Archive celebrates his work – it’s an incredible resource and a fascinating insight into the 1970s, in Manchester and beyond.

Dave Haslam

Admin note. Mike Don's obituary in The Guardian can be found here:

www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jul/04/mike-don-...Below is an introduction by Mike Don, the backbone of Mole Express:

Mole Express was, by one yardstick, one of the most successful of Britain's 'alternative' periodicals With 57 editions over a seven year period (1970-1977) In other respects, though, it passed completely below the popular radar Just to give an example; Manchester's Central Library received a copy of every edition, but many of them were discarded allegedly on the grounds, I was later told, that Mole Express "was not a Manchester paper" And I still meet people who remember it - "you used to run that paper the Red Mole / Manchester Free Press, didn't you?"

(for the record, the 'Freep' was a local competitor, and the 'Red Mole' a London-based Trotskyist rag)

I've made several attempts to write this introduction, only to scrap them when they began to turn into a potted history. I've tried to keep the account general, without too much detail, most of which would in any event be anecdotal, reliant on my imperfect memory, and sometimes of interest to m'learned friends at Sue Grabbitt & Runne

It has to be said that the Mole was for most of its life very much my personal baby. Extending through three different formats, four (at least) printers and an ever-changing editorial team with myself as the one common factor. After writing that, I thought of an interesting comparison; my relationship to Mole Express was in certain respects analogous to that of the late Mark E Smith to The Fall. That is, a single somewhat bloody-minded individual determinedly keeping the flame, continuously re-inventing its approach through different incarnations, and reflecting changes in the wider society.

I don't think anybody at Mole ever paid much heed of the paper's role in a wider social context. People at the sharp end rarely do, going on about the zeitgeist and such marks you out as a pretentious plonker and candidate for Pseuds Corner. Mostly it was an endless running crisis between getting copy for the next issue and paying for the last one. But with the benefit of hindsight, comparing the approach of Mole over the years to the political climate of the day does reveal an interesting, and not coincidental, relationship.

Thus, the first five issues, from 1970, at the fag-end of the hippy-trippy 60s, looked as though they'd been slapped together on the kitchen table of a stoner commune. Which they more or less were, actually. From no.6, with a new printer and an entirely new team (apart from your humble narrator) Mole* became first a more, well, conventional 'underground paper' with a wider range of material, including reprinted items from the 'Underground Press Syndicate'. Within a few issues this had metamorphosed - it being the early stages of Edward Heath's Tory government - into an overtly political, anti-Conservative, paper, though retaining a lot of the countercultural material of yore. It wasn't, so far as I recall, a conscious decision, we were never that organised, just something that seemed fitting at the time.

The peak intensity of this period came with several editions using 'newspaper' style front covers relating to key events of the time, the National Front and the Angry Brigade trial. In their pomp the NF were a severe pain in the backside to anyone remotely leftwing. They didn't - couldn't - hide their full-on Nazi background, unlike their milquetoast successors. As for the Angries - I still get goosebumps when recalling that at least one issue of Mole was largely written and pasted up (no word processors then) by folk who a week or two later would be arrested as (allegedly - one of them was acquitted) key Angry Brigade bombers.

After that excitement - from arrests to verdicts was some fourteen months - the content became gradually less incendiary. Early Mole had been ferociously anarchist, even Situationist - calling your what's on guide 'The Spectacle' is something of a giveaway - but by 1975 the material was increasingly local and investigative. Again, as with the change in 1971, it may well have reflected, although not consciously noted at the time, the national political climate, with the election of a Labour government in 1974.

Mole's 'last hurrah' in 1976/7 saw yet another change in format, printer, and personnel. A slimline editorial team of three with a final ignominious and abrupt end when one of the three threatened to sue the other two for libel. Subsequently the two survivors started a successor, the 'City Enquirer' which appeared every 2-3 weeks until 1980. But that's another story

Mole was never the go-to journal for deathless prose. Most of the copy was written either by me or by one or other of the current editing team (I certainly typed most of it!). As we were pretty well honing our journalistic skills 'on the job' this produced an unavoidable amateurishness. Feature articles by outside contributors were prized. Less work involved, and generally better written. Particularly those by professional journalists: 'Bush Telegraph' came VERY anonymously - from a Daily Telegraph scribe who subsequently jumped ship to become one of the founders of the 'New Manchester Review'. And for a number of issues the 'Media Burn' gossip column was supplied by a chap from the Daily Mail.

While a few contributors used their own names, pseudonyms were often preferred. With the passage of over 40 years since Mole breathed its last, I have forgotten some of them; I do recall, though, that 'Joe Fernwright' was Dave Geall (college lecturer, and incidentally co-founder of Grass Roots Books), while Gully Foyle' who contributed an occasional column entitled 'I Sing The Body Electric' was no less a celebrity than the late Roger Eagle. Incidentally 'Fernwright', 'Foyle' and 'Body Electric' are all science fiction references, to Dick's 'Galactic Pot-Healer', Bester's 'Tiger Tiger' and Ray Bradbury respectively. Another anonymous or pseudonymous contributor in the 1975/6 period was 'Martin Zero' (aka Martin Hannett, the legendary Factory Records recording genius). I'm uncertain of his Mole nom-de-plume; possibly 'Flash Rat'.

Apart from the odd contributed piece like 'Bush Telegraph', Mole's own journalistic efforts were not exactly at the cutting edge "Scoops" were rare - given the 6-8 weeks between editions, any worthwhile story would be whiskery old news by the time it appeared on the newsstands. On that front, Mole might pass into history as a mere footnote, with just a consolation prize for longevity. The one field, however, where it could hold its head high, with few to match it, was in the field of cartoons and political graphics. Contributors on that front included nationally-known artists like Hunt Emerson, Tony Husband (aka 'Ant'), Ray Lowry, and the near-legendary Bill Tidy. Along with lesser-known names -Pete Rigg, 'Caz', JH Szostek, Dave Kay, Martin Sudden.

Undoubtedly the most severely under-rated artist of them all was Pete Kirkham, whose distinctive style -from cover art and centre-spread features down to the funny little column headers like that for ' Media Burn' really deserved a wider audience that the few hundred of Mole's regular readership (Print run was generally around 1500-2000, but not all of these were sold).

Artwork aside, perhaps the abiding value of Mole Express is to future social historians, a fractured - and rather grubby - window to the Manchester of 40-odd years ago, in some respects an era seemingly as distant as the Victorians. Just look at the display ads (particularly for those without 20/20 vision!). Who now remembers Black Sedan or Gold Seal? Or Orbit Books, Stoneground and Gordons where the premises have not just changed hands but physically disappeared. Mole didn't have any great difficulty getting ads; but sometimes considerable difficulty getting the advertisers to pay up.

'*The paper was originally titled just 'Moul', a name devised by Sue Lear, its founder Derivation obscure. When Sue left, I got rather pee'd off with people talking about 'Mowl Express' and changed it. (Written 2018).

Mole Express was a truly alternative, grass-roots publication first issued in 1970 which ran for seven years. Throughout its 57 issues the modern reader catches a glimpse of the anarcho, post-hippy subculture in Manchester (and sometimes wider afield).

Mole Express was a truly alternative, grass-roots publication first issued in 1970 which ran for seven years. Throughout its 57 issues the modern reader catches a glimpse of the anarcho, post-hippy subculture in Manchester (and sometimes wider afield).